Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS) is a serious, sometimes life-threatening condition affecting dogs. It encompasses a range of anatomical abnormalities in the upper airways, resulting in breathing difficulties and subsequent exercise and heat intolerance. It is a progressive disorder, which means it gets worse over time. The primary method of treatment is surgery.

Any difficulties in breathing are abnormal and should not be present in a healthy dog, no matter what breed it is.

Brachycephalic - meaning ‘short-skulled’ - refers to the type of dogs predisposed to this syndrome. Brachycephalic can refer to dog breeds, such as Boston Terriers, English Bulldogs, French Bulldogs, and Pugs, as well as individual dogs that may be of mixed breed. While not every brachycephalic dog will develop BOAS, they commonly show at least some clinical signs.

A recent study has shown that while many people recognise and report signs consistent with BOAS in their dogs, these signs are often dismissed as ‘normal for the breed’ (Packer et. al 2019). Any difficulties in breathing are abnormal and should not be present in a healthy dog, regardless of breed. We want dogs to be as happy and healthy as possible: being aware of the symptoms of BOAS and managing the condition will go a long way towards improving our companions' quality of life.

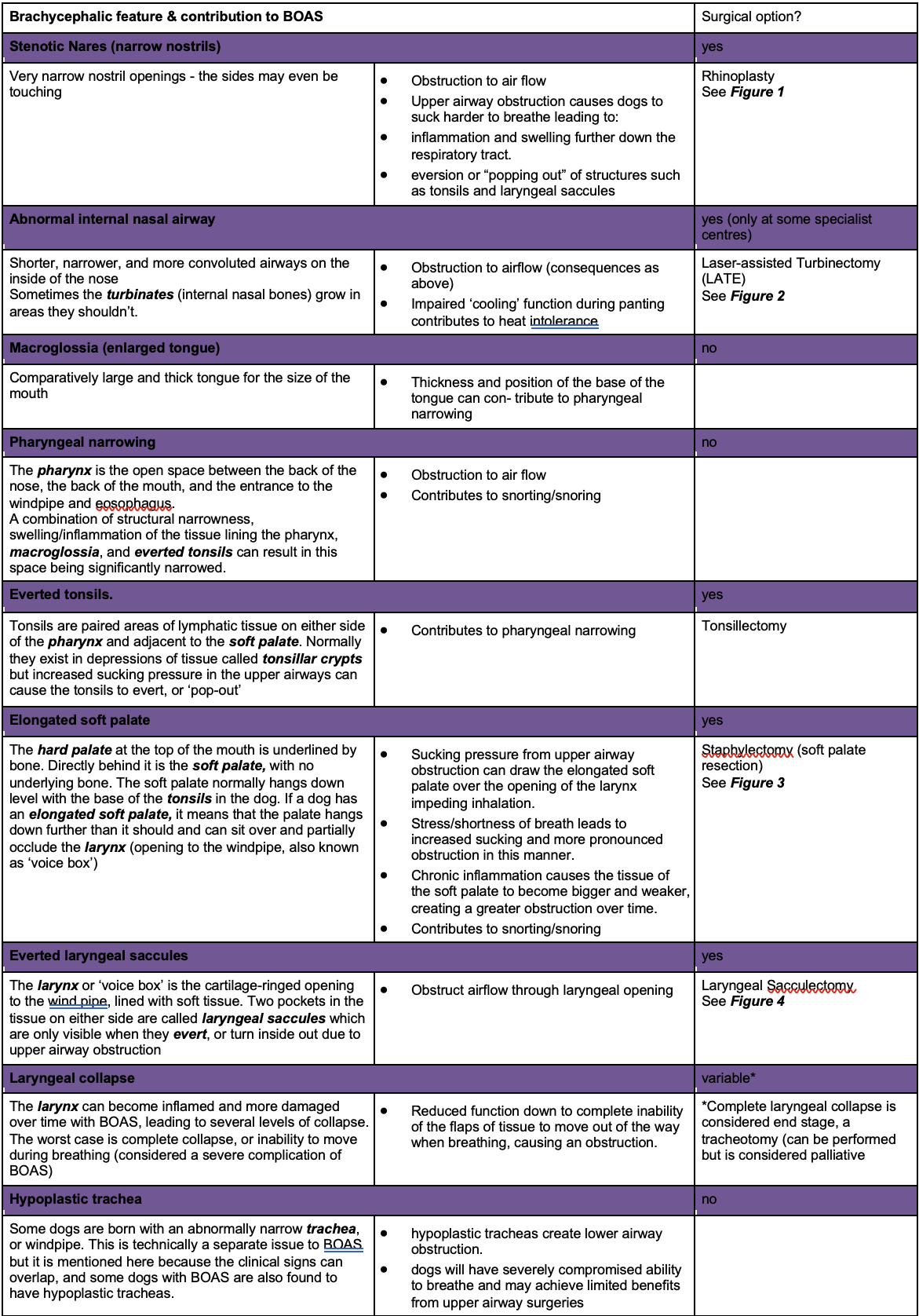

BOAS is a syndrome caused by a complex combination of anatomical traits found in brachycephalic dogs, resulting in difficulty drawing breath and regulating temperature. The following table lists these traits, why they cause problems, and if there is a surgical procedure to address that feature. Dogs may have some or all these features. Many are a result of dogs being selectively bred to attain shorter snout lengths: the bones of the skull decrease in length, but the internal tissues do not shorten at the same rate, resulting in the ‘compaction’ of the inner tissues.

Dogs with a combination of the below factors can find breathing remarkably difficult under normal circumstances. Imagine these same dogs in stressful situations, hot environments, or during exercise: increased breathing effort can quickly develop into an obstructive breathing episode. Being ‘air hungry’ but unable to take a deep breath can understandably cause some dogs to panic, which can lead to a vicious cycle where rapid shallow breathing can result in collapse and even death. The good news is that early surgical intervention can markedly improve dogs’ ability to breathe and reduce the risk of them encountering a life-threatening episode.

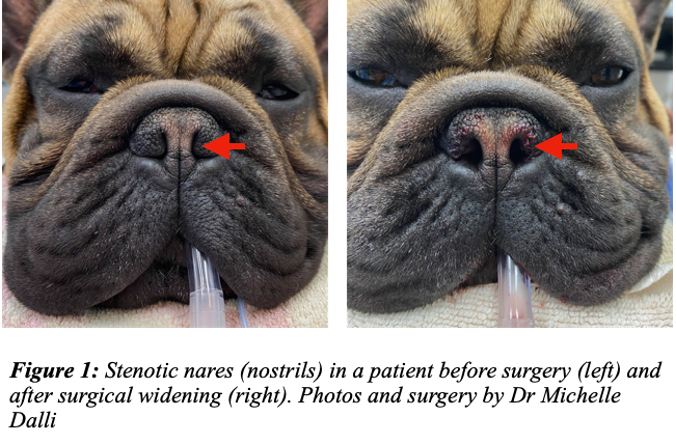

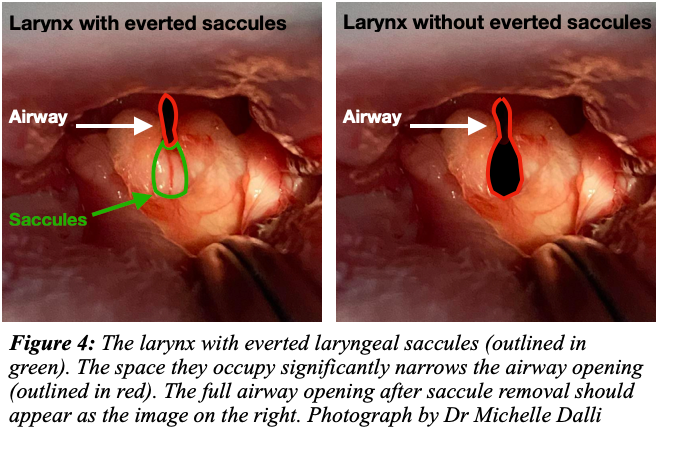

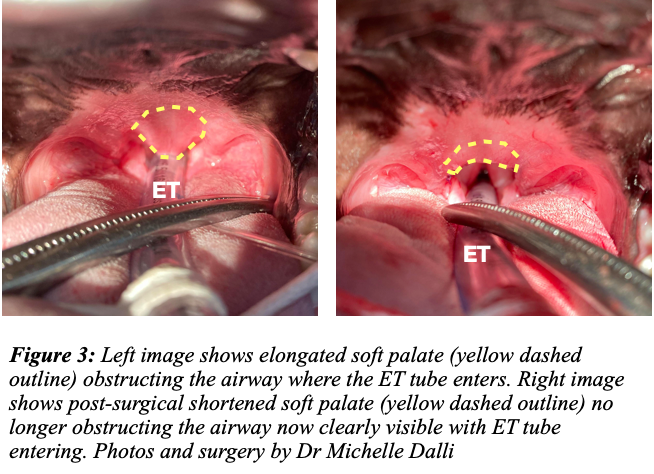

Visual examination can identify stenotic nares. However, a general anaesthetic is necessary to identify elongated soft palate and everted laryngeal saccules, as they are internal.

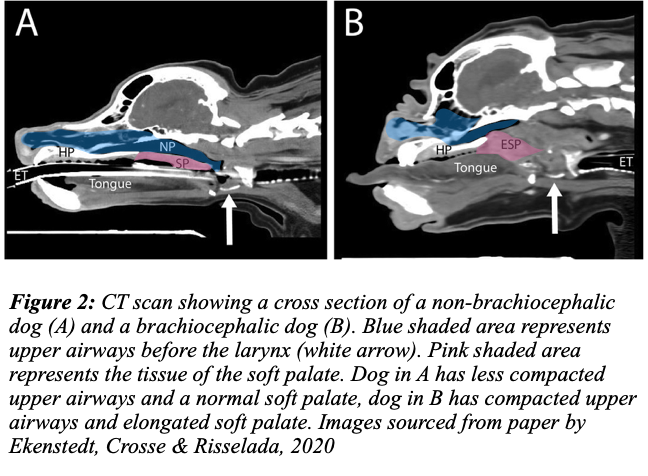

Some sources recommend endoscopy and CT to fully evaluate internal structural changes (e.g., CT scan in Fig 2). We can pursue this assessment type if the owner prefers as we now have our own CT scanner and endoscopy equipment.

As BOAS dogs have increased anaesthetic risk due to impaired breathing and increased chance of regurgitation, we try to minimise the number of anaesthetics they undergo. To this end, it is preferable to have only one anaesthetic where we both identify and repair internal abnormalities, so the final diagnosis of the elongated soft palate and everted laryngeal saccules will occur on the day of the surgery.

We now have a system to objectively grade brachycephalic dogs by examining them before and after exercise. Two of our veterinarians have been accredited to perform this grading, which is recommended for all breeding animals to determine how affected they are by BOAS and to help reduce the incidence of BOAS in their breed. The test takes only 10 minutes and can also be utilised in pet dogs to determine whether they require surgery.

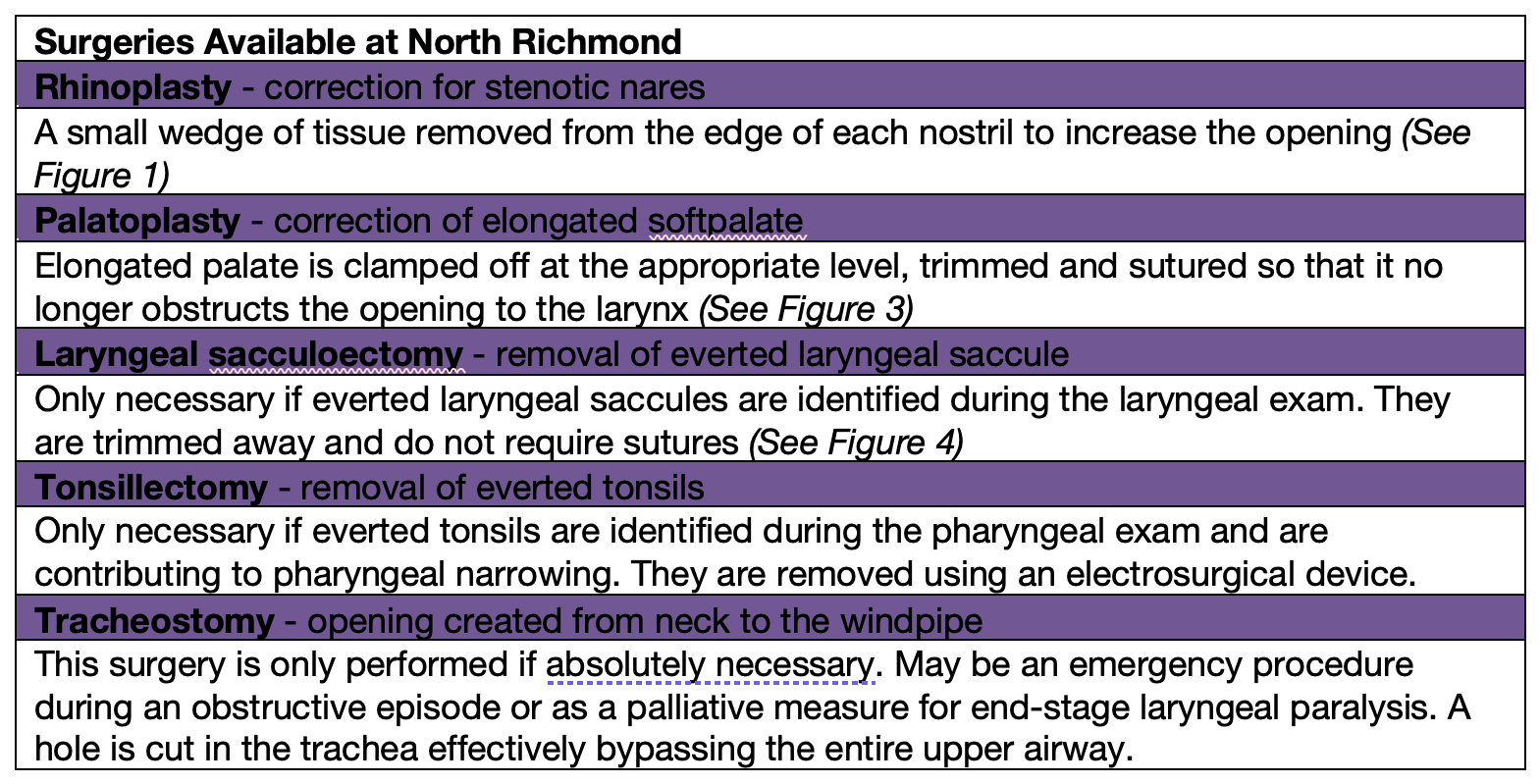

Surgical correction of stenotic nares, elongated soft palate, and surgical resection of everted laryngeal saccules are the primary treatments for dogs with BOAS. Additional laser surgeries have been introduced at specialist centres to target abnormal turbinate bones (further discussion below). As the problems are structural, medicines are not adequate treatment methods, and non-surgical options for the disease are considered palliative.

Dogs with BOAS must undergo corrective surgery as without it they are susceptible to heat and exercise and there is a genuine chance of death by suffocation during an obstructive breathing episode. The longer a dog goes with untreated BOAS, the greater the compromise of the respiratory tract and the more likely it is to develop more severe secondary problems such as everted laryngeal saccules, thickening of tissues and laryngeal collapse. To minimise these negative time-based changes, we recommend early surgical intervention.

Surgery at our hospital costs anywhere from $1500 to $5000, depending on how many procedures are performed and if pre-surgical tests such as blood work or CT scans are performed. A detailed estimate can be given at the time of consultation.

In recent years, a type of surgery that addresses the narrowing and/or overgrowth of tissue in the internal nasal passageways has been introduced. As this anatomical region is difficult to visualise and alter it has not been traditionally treated as part of BOAS surgeries. With the availability of advanced imaging techniques (CT scans), abnormalities in these structures have begun to be identified and treated. A surgical laser is used to burn away aberrant tissue inside the nose so that an open passageway exists between the inside of the nostrils back to the nasopharynx (area above the soft palate).

We do not offer this surgery at North Richmond Vet as it requires specialised equipment and expertise that we currently need to possess. Dogs may also require extended hospitalisation and 24-hour care after this procedure, which we currently do not provide.

A study of traditional surgical treatments found that 70% of dogs had improvement in clinical signs with nares and palate surgery alone (Seneviratne, Kaye & Haar 2020)

The laser procedures are still relatively new. While there are certainly studies supporting their use, even within those studies, it is not recommended as a stand-alone procedure: the traditional surgeries (nares and soft palate) are still necessary. One group considered dogs as candidates for this procedure only when they still had marked respiratory difficulty after the initial surgeries (Liu et al 2018). The results of these surgeries have been promising but it is essential to understand that it is still not a magic fix and even when successful, the aberrant turbinates can grow back over time.

Once your pet is home after surgery, it will require extra care from you. This will include keeping your pet quiet and limiting activity for 2 weeks. Feeding soft food and supervising feeding is recommended to reduce the chance of aspiration. Give the prescribed medication and monitor your pet's breathing. We provide 24-hour emergency services to our patients if there are any concerns once they are home.

Most dogs recover after 2 weeks and owners can start exercising and return to normal activities afterwards. We provide free post-op consultations to check on how your pet is recovering and their respiratory function after surgery.

While anaesthetics are monitored and surgeries performed with the utmost care, there is always some risk of complication. Apart from the usual anaesthetic risks associated with any surgical procedure, BOAS dogs are already at a higher risk due to their impaired breathing and increased chance of regurgitation post-operatively. Obesity also increases the chance of complications and is a common issue in dogs who are unable to perform much exercise.

The most common post-surgical complications associated with these procedures are related to regurgitation (which could lead to choking or aspiration pneumonia) and severe swelling which can in turn obstruct the airway. Specific individuals have an increased sense of panic at their shortness of breath; we may need to give sedative medication to these patients to reduce the chance of an obstruction. We reduce the likelihood of these complications by fasting our patients for at least 12 hours before surgery and giving anti-vomiting and anti-inflammatory medication. Our nurses keep the ET tubes in as long as possible to maintain a patent airway and monitor dogs who have had BOAS surgery very closely until they are fully conscious.

We also plan to do surgeries early in the day and send our patients home the same day as surgery. We find this reduces anxiety and stress in these unique patients and the complications are reduced dramatically by taking this approach.

BOAS dogs who do not undergo surgery are at risk of suffocation - so regardless of surgical and anaesthetic risk, it is still the best option for a good quality of life in these patients.

It is essential to be realistic about what can be achieved regarding treatment for your dog if it is diagnosed with BOAS. Importantly, surgery improves respiratory function in most dogs; however, due to limitations in surgical interventions, most dogs will still have some respiratory compromise, i.e., there will never be a complete resolution of their condition. This is because certain aspects contributing to BOAS cannot be changed - e.g., the thickness of the tongue, narrowness of the trachea, and shortness of upper airways. Most dogs do quite well in the long term after undergoing surgical management of their condition. Some dogs, even with surgery, may not have as long a life due to the severity of their signs before surgery. Each dog is an individual and your veterinarian will discuss individual expectations and outcomes with you. It is still important not to expose dogs to excessive heat and to be aware of their limits when exercising even post-surgery.

In rare cases, despite surgery, a patient may not be able to regain good respiratory function. This can be partly due to some parts of the respiratory system that we cannot alter surgically. If so, your veterinarian may discuss a referral for LATE surgery or other surgical options such as laryngeal surgery or a permanent tracheostomy.

We believe the above covers the information you need to understand your dog’s condition and the treatments we can offer you at North Richmond. References are provided below which you can consult if you want more in-depth information; otherwise, don’t hesitate to call us or book a consultation to discuss anything further with your veterinarian.

Written by Dr Teela Brown, BVSc, BSc(Vet) (Hons I)

References

Ekenstedt, KJ, Crosse, KR, & Risselada, M ‘Canine Brachycephaly: Anatomy, Pathology, Genetics and Welfare’, J. Comp. Path. Vol. 176, 109e115, 2020

Liu, N-C, Genain, M-A, Kalmar, L, Sargan, DR, & Ladlow, JF ‘Objective effectiveness of and indications for laser-assisted turbinectomy in brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome’, Veterinary Surgery 2018;1–9. https://doi.org/10. 1111/vsu.13107 2018

Packer, RMA, O’Neill, DG, Fletcher, F, & Farnworth, MJ ‘Great expectations, inconvenient truths, and the paradoxes of the dog-owner relationship for owners of brachycephalic dogs’, PLoS ONE 14(7): e0219918. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0219918, 2020

Seneviratne, M, Kaye, BM, & Haar, GT ‘Prognostic indicators of short-term outcome in dogs undergoing surgery for brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome’, Veterinary Record, doi: 10.1136/vr.105624, 2020

Torrez, CV, & Hunt, GB ‘Results of surgical correction of abnormalities associated with brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome in dogs in Australia’, Journal of Small Animal Practice, 47, 150–154, 2006

P: 02 4571 2042

E: northrichmondvet@hotmail.com

Copyright © 2022 North Richmond Vet Hospital